Consistency and Consensus

Fault tolerance in distributed systems refers to the ability to maintain service functionality even if some internal component fails. One way to achieve this is to let the service crash and show an error message to the user when the service fails. However, a more effective approach is to use abstractions that provide useful guarantees, such as transactions which hide issues like crashes, concurrent access, and storage device failures from the application. This allows the application to operate as if these problems do not exist.

Consistency Guarantees

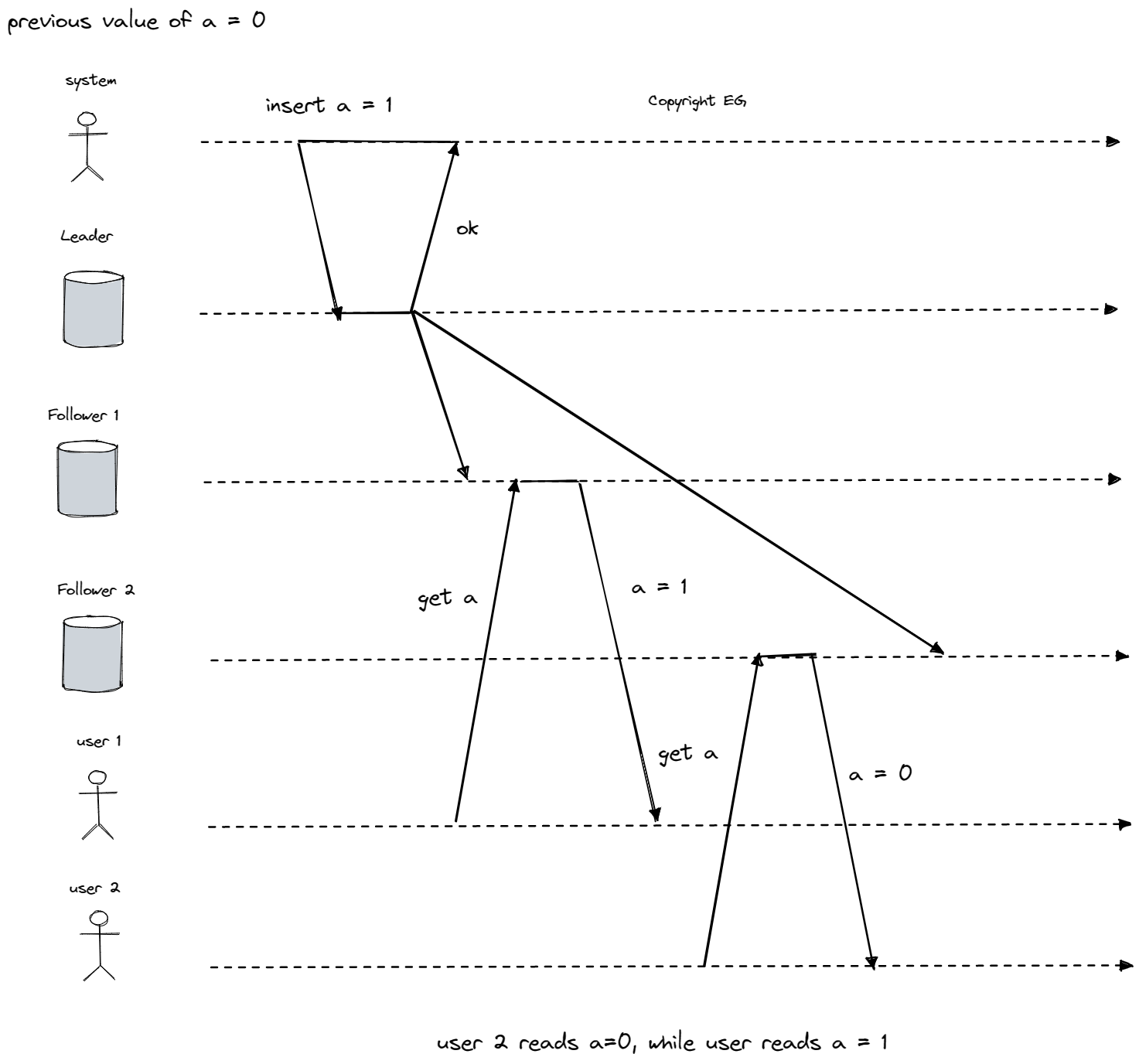

In a replicated database, write requests may arrive at different nodes at different times, resulting in temporary inconsistency that eventually resolves itself through convergence. While some databases offer strong consistency guarantees, others only provide eventual consistency (you can think of it as convergence to the same state), which requires a certain level of awareness of its limitations. It's important to note that while stronger consistency guarantees may improve the accuracy of data, they may also come with trade-offs in terms of performance and fault tolerance.

Linearizability

An eventually consistent database can cause confusion because if you request the same information from two different replicas at the same time, you may receive different answers. It would be more straightforward if the database appeared to have only one replica, providing all clients with the same view of the data and eliminating the need to consider replication lag.

Linearizability and serializability are two different guarantees in databases. While both terms refer to the concept of arranging operations in a sequential order, they have distinct meanings and applications.

Serializability is an isolation property that applies to transactions, which are groups of operations that read and write multiple objects (such as rows, documents, or records). It guarantees that transactions behave as if they were executed in a specific order, even if the actual order of execution is different.

Linearizability, on the other hand, is a recency guarantee for reads and writes of a single object. It does not group operations into transactions, and does not prevent issues such as write skew unless additional measures are taken.

A database may provide both serializability and linearizability, which is known as strong one-copy serializability (strong-1SR). Some implementations of serializability, such as two-phase locking and actual serial execution, are also linearizable. However, serializable snapshot isolation is not linearizable because it relies on consistent snapshots that do not include more recent writes, which means reads from the snapshot are not linearizable.

Locking and leader election

A system that uses single-leader replication needs to ensure that there is only one leader, not multiple leaders (a situation known as split brain). One way to achieve this is to use a lock that is acquired by nodes when they start up. The node that successfully acquires the lock becomes the leader. However, for the lock to be effective, it must be linearizable, meaning that all nodes must agree on which node owns the lock. Otherwise, it could leave to unexpected behavior.

Constraints and uniqueness guarantees

Linearizability is necessary for enforcing uniqueness constraints in databases. For example, a username or email address must uniquely identify a single user, and a file storage service cannot have two files with the same path and filename. To ensure that these constraints are enforced as data is written, linearizability is required.

This process is similar to acquiring a lock, where a user "locks" their chosen username when registering for a service. It is also similar to an atomic compare-and-set operation, where the username is set to the user's ID if it is not already taken.

Implementing Linearizable Systems

Linearizability is a property that ensures a system behaves as if there is only one copy of the data and all operations on it are atomic. One way to implement a system with linearizable semantics is to use a single copy of the data, but this approach is not fault-tolerant. A more common approach is to use replication, but different types of replication offer varying levels of linearizability:

- Single-leader replication: In a system with single-leader replication, the leader maintains the primary copy of the data and followers have backup copies. If reads are made from the leader or synchronously updated followers, they have the potential to be linearizable. However, not all single-leader databases are linearizable, either by design or due to concurrency bugs.

- Consensus algorithms: Some consensus algorithms, such as ZooKeeper and etcd, can implement linearizable storage safely due to measures that prevent split brain and stale replicas.

- Multi-leader replication: Systems with multi-leader replication are generally not linearizable because they concurrently process writes on multiple nodes and asynchronously replicate them to other nodes, leading to conflicts that require resolution.

- Leaderless replication: Depending on the configuration and definition of strong consistency, leaderless replication may not be linearizable. Conflict resolution methods based on time-of-day clocks and sloppy quorums are almost certainly nonlinearizable, and even with strict quorums, nonlinearizable behavior is possible.

The Cost of Linearizability

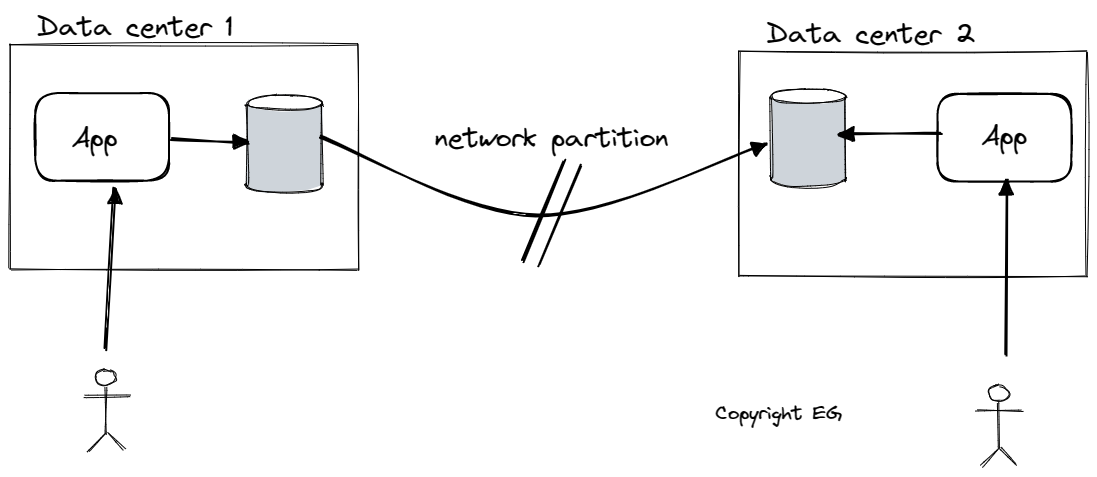

In a scenario where there is a network interruption between two datacenters, the behavior of a multi-leader database and a single-leader database will differ. In a multi-leader database, each datacenter can continue operating normally since writes are asynchronously replicated and queued until connectivity is restored. However, in a single-leader database, the leader must be in one of the datacenters, and any writes and linearizable reads must be sent synchronously to the leader. If the network between datacenters is interrupted, clients connected to a follower datacenter cannot contact the leader and are unable to make linearizable reads or writes, causing an outage for the application in those datacenters until the network link is repaired. Clients that can connect directly to the leader datacenter are not affected.

The CAP theorem

The CAP theorem, which states that a distributed system can only have two out of three desirable properties (Consistency, Availability, and Partition tolerance), is often presented as a choice between two properties. However, this is misleading because network partitions are a type of fault that will occur regardless of the system's design. As such, it is not a choice whether to have partition tolerance, but rather a matter of how the system will handle it.

Any linearizable database, regardless of its implementation, may experience issues when some replicas are disconnected from the rest due to network problems. In these situations, replicas that require linearizability will be unable to process requests and become unavailable until the network problem is resolved. On the other hand, if the application does not require linearizability, each replica can process requests independently, even if it is disconnected from other replicas. This allows the application to remain available in the face of network problems, but its behavior is not linearizable.

The decision to trade linearizability for performance, as seen in the multi-core memory consistency model and some distributed databases, is not motivated by the need for fault tolerance but rather by the desire for improved performance. Linearizability can be slow and this is true even in the absence of network faults. In these cases, the choice to not provide linearizable guarantees is primarily driven by the need for increased performance.

Ordering Guarantees

In computer science, total order is a relationship between elements in a set that allows any two elements to be compared. For example, a set of natural numbers is totally ordered because for any two numbers in the set, one is either greater than, less than, or equal to the other.

Causality is a partial order, not a total order. Two events are causally related if one event caused the other. In a causal order, events are ordered based on their causal relationships, but events that are concurrent (i.e., not causally related) are incomparable.

Consistency models in distributed systems refer to the ways in which different copies of data are kept synchronized across multiple nodes or servers. One such model is linearizability, which requires that the system behaves as if there is only a single copy of the data and that all operations are carried out in a total order. This means that if two operations are performed on the data, it is clear which one happened before the other.

Another consistency model is causality, which orders events based on their causal relationship. This means that if one event causes another event to occur, the first event is considered to happen before the second event. Causality defines a partial order, as it is possible for events to be concurrent and therefore incomparable.

To implement causality, a database needs to know which version of the data was read by the application. This can be achieved by passing the version number from the prior operation back to the database on a write. In a single-leader replication system, the leader can assign a monotonically increasing sequence number to each operation in the replication log. However, in a multi-leader or leaderless database, it is more challenging to generate sequence numbers that are consistent with causality.

One solution is to use Lamport timestamps:

In a distributed system, each node has a unique identifier and maintains a counter of the number of operations it has processed. The Lamport timestamp for an operation is then a combination of the counter value and the node ID, represented as a pair (counter, node ID). Lamport timestamps provide a total order, with a greater counter value indicating a greater timestamp. If the counter values are the same, the node ID is used to determine the order, with a greater node ID indicating a greater timestamp.

To ensure that the ordering from the Lamport timestamp is consistent with causality, every node and client in the system keeps track of the maximum counter value it has seen so far, and includes that maximum on every request. When a node receives a request or response with a maximum counter value greater than its own counter value, it immediately increases its own counter to that maximum. As long as the maximum counter value is carried along with every operation, this ensures that the ordering from the Lamport timestamp accurately reflects the causality of the operations in the distributed system.

Total order of operation refers to the order in which operations are carried out in a distributed system. This order only emerges after all of the operations have been collected. Total order broadcast is a technique that ensures reliable and totally ordered delivery of messages in a distributed system. This means that if a message is delivered to one node, it is delivered to all nodes, and that the messages are delivered to every node in the same order. Systems like ZooKeeper and etcd implement total order broadcast.

Total order broadcast can be used to build linearizable storage on top of it. If every message represents a write to the database, and every replica processes the same writes in the same order, the replicas will remain consistent with each other. However, total order broadcast alone does not guarantee linearizable reads. To make reads linearizable, there are a few options: sequencing reads through the log, fetching the position of the latest log message in a linearizable way, or making the read from a replica that is synchronously updated on writes. Another option is to attach a sequence number to each message sent through total order broadcast, using a linearizable integer to ensure that the messages are delivered consecutively by sequence number.

Distributed Transactions and Consensus

Consensus is a crucial and fundamental challenge in distributed computing. At its core, the goal of consensus is to get multiple nodes to agree on a particular issue. While this might seem straightforward, many systems have struggled to effectively solve this problem due to the assumption that it is simple to achieve. In reality, achieving consensus among multiple nodes can be a complex and difficult task. Now let's go through two examples of real situation where consensus is needed:

- Leader election is a process in which all nodes in a database with single-leader replication must agree on which node is the leader. If some nodes are unable to communicate with others due to a network fault, the leadership position may become contested. In this case, it is important to achieve consensus to avoid a split brain situation in which two nodes both believe themselves to be the leader, leading to inconsistency and data loss.

- In a database that supports transactions across multiple nodes or partitions, there is the possibility that a transaction may fail on some nodes but succeed on others. In order to maintain the atomicity of transactions, it is necessary to get all nodes to agree on the outcome of the transaction. This is known as the atomic commit problem and requires achieving consensus.

Atomic Commit and Two-Phase Commit (2PC)

In a database, a transaction either successfully commits or aborts. Atomicity ensures that the transaction is either fully completed or not completed at all, preventing incomplete or half-finished results.

On a single node, the commitment of a transaction depends on the order in which the data is written to disk, with the data written first followed by the commit record.

Two-Phase Commit (2PC) is a protocol for ensuring the atomicity of transactions that span multiple nodes. It uses a coordinator (also known as a transaction manager) to facilitate the commit process. When the application is ready to commit, the coordinator begins phase 1 by sending a prepare request to each of the participating nodes, asking whether they are able to commit. If all participants reply "yes", the coordinator moves to phase 2 and sends a commit request to all nodes, causing the commit to take place. If any of the participants replies "no", the coordinator sends an abort request to all nodes in phase 2. When a participant votes "yes", it promises that it will definitely be able to commit later, and this promise ensures the atomicity of 2PC.

If there is a failure during 2PC (such as a prepare request failing or timing out), the coordinator aborts the transaction. If any commit or abort requests fail, the coordinator retries them indefinitely. If the coordinator fails before sending the prepare requests, a participant can safely abort the transaction. The only way for 2PC to complete is for the coordinator to recover in the event of a failure, which is why the coordinator must write its commit or abort decision to a transaction log on disk before sending commit or abort requests to participants.

Three-Phase Commit (3PC) is an alternative to 2PC that requires a perfect failure detector. It is a non-blocking atomic commit protocol that does not become stuck waiting for the coordinator to recover. However, it requires additional infrastructure and is not widely used.

Distributed transactions carry a significant performance penalty due to the disk forcing and additional network round-trips required for crash recovery in 2PC. The XA (eXtended Architecture) standard provides a way to implement two-phase commit across different technologies, and it is supported by many traditional relational databases and message brokers.

Locking is another technique used to ensure the atomicity of transactions. In a database, transactions typically take a row-level exclusive lock on any rows they modify to prevent dirty writes. While these locks are held, no other transactions can modify the locked rows. If a coordinator fails, orphaned in-doubt transactions may occur, and an administrator must manually decide whether to commit or roll back the transaction.

Fault-Tolerant Consensus

In a consensus algorithm, one or more nodes may propose values, and the algorithm determines which values to accept. To be effective, the consensus algorithm must satisfy several properties:

- uniform agreement (no two nodes decide differently)

- integrity (no node decides twice)

- validity (if a node decides on a value, that value was proposed by some node)

- termination (every node that does not crash eventually decides on a value).

If fault tolerance is not a concern, it is easy to satisfy the first three properties by simply designating one node as the "dictator" and allowing it to make all of the decisions. The termination property, on the other hand, is related to fault tolerance, as it ensures that even if some nodes fail, the remaining nodes can still reach a decision. This property is known as liveness, whereas the other three properties are known as safety properties.

There are several well-known fault-tolerant consensus algorithms, including Viewstamped Replication (VSR), Paxos, Raft, and Zab.

Total order broadcast, which ensures the reliable and totally ordered delivery of messages to all nodes, can be seen as equivalent to repeated rounds of consensus. Total order broadcast ensures the reliable and totally ordered delivery of messages to all nodes, which is equivalent to repeatedly performing consensus to decide on the order of message delivery. In each round, nodes propose the next message they want to send and then decide on the order of message delivery. The agreement property ensures that all nodes decide to deliver the same messages in the same order, the integrity property prevents duplicate messages, the validity property ensures that messages are not corrupted, and the termination property ensures that messages are not lost.

Single-leader Replication and Consensus

Consensus protocols typically use a leader to coordinate decision-making, but they do not guarantee that there is only one leader at a time. Instead, they define an epoch number (also called a ballot number in Paxos, a view number in Viewstamped Replication, and a term number in Raft) that identifies the current leader. Within each epoch, there is a unique leader. When the current leader is believed to have failed, the nodes start a vote to elect a new leader, incrementing the epoch number in the process. If there is a conflict, the leader with the higher epoch number prevails.

For every decision a leader wants to make, it must send the proposed value to the other nodes and wait for a quorum (majority) of nodes to vote in favor of the proposal. This process is similar to synchronous replication, and it requires a strict majority of nodes to operate. Most consensus algorithms assume a fixed set of nodes that participate in voting, making it difficult to add or remove nodes from the cluster. Dynamic membership extensions are less well understood than static membership algorithms.

Consensus systems rely on timeouts to detect failed nodes, but in geographically distributed systems, network issues can sometimes cause a node to falsely believe that the leader has failed, leading to frequent leader elections and poor performance.

Membership and Coordination Services

ZooKeeper and etcd are often described as "distributed key-value stores" or "coordination and configuration services." They are designed to hold small amounts of data that can fit entirely in memory, and they use a fault-tolerant total order broadcast algorithm to replicate the data across all the nodes. ZooKeeper is modeled after Google's Chubby lock service and provides several useful features, including:

- Linearizable atomic operations (using compare-and-set operation to implement lock)

- Total ordering of operations (using fencing for conflict resolution)

- Failure detection (ZooKepper automatically releases locks when session is declared dead)

- Change notifications (client can observe/watch for changes).

It is particularly useful for distributed coordination, such as choosing a leader or primary among multiple instances of a process or service.

ZooKeeper and similar services are not intended for storing the runtime state of an application, but are more suitable for slow-changing data like the identity of a leader for a particular partition. Other tools, such as Apache BookKeeper, are better suited for replicating application state.

These services are also often used for service discovery, allowing clients to find the IP address of a particular service. In cloud environments, where virtual machines may come and go, it is common for services to register their network endpoints in a service registry so that they can be found by other services. ZooKeeper and similar tools can be seen as part of a long history of research into membership services, which help determine which nodes are currently active and live members of a cluster.

Summary

Consistency and consensus are important topics in distributed computing that ensure that data is accurate and reliable in a distributed system. Linearizability is a popular consistency model that aims to make replicated data appear as though there is only a single copy and to make all operations act on it atomically. While linearizability is easy to understand and makes a database behave like a variable in a single-threaded program, it can be slow and is particularly sensitive to large network delays. On the other hand, causality imposes an ordering on events in a system based on cause and effect and allows for some concurrency. While causal consistency does not have the coordination overhead of linearizability and is less sensitive to network problems, it is not sufficient to solve certain problems such as ensuring the uniqueness of a username during concurrent registrations. In these cases, we must turn to consensus, which ensures that all nodes agree on a decision and that the decision is irrevocable. Several problems, including atomic transaction commit, total order broadcast, locks and leases, membership services, and uniqueness constraints, can be reduced to and solved through consensus. To handle the failure of a single leader, we can either wait for the leader to recover, manually fail over to a new leader, or use a fault-tolerant consensus algorithm such as Viewstamped Replication, Paxos, Raft, or Zab. These algorithms allow for the replacement of a failed leader and ensure that the system can continue to make progress even in the event of failures.