Stream Processing

In Batch Processing, we learned about batch processing, a technique that processes a set of input files to produce a new set of output files. Batch processing assumes that the input data is of a known and finite size and can be completed within a specific time period. However, in reality, a lot of data is unbounded and arrives gradually over time, making it difficult to use traditional batch processing techniques. Stream processing is a method of continuously processing data as it arrives, rather than waiting for a fixed time period or until all the data is received. we will explore the representation, storage, and transmission of streams, the relationship between streams and databases, and approaches and tools for continuously processing streams to build applications.

Transmitting Event Streams

Records, also known as events, are data that represent something that has happened at a specific point in time, often including a timestamp. Events are generated by producers and may be processed by multiple consumers. Groups of related events are often organized into topics or streams. In the past, producers and consumers were connected through the use of files or databases, with producers writing events to the datastore and consumers periodically polling the datastore for new events. However, this method becomes inefficient when moving towards continuous processing, as it is better for consumers to be notified of new events as they occur. To address this, databases offer triggers, but these can be limited, leading to the development of specialized tools for delivering event notifications.

Messaging Systems

In the publish/subscribe model, there are different approaches to handling situations where producers send messages faster than consumers can process them, or where nodes crash or go offline. These approaches include dropping messages, buffering messages in a queue, or applying backpressure to block producers from sending more messages. There are also systems that use direct communication between producers and consumers without intermediaries, such as UDP multicast, brokerless messaging libraries, and direct HTTP or RPC requests. However, these systems require application code to be aware of the possibility of message loss and can only tolerate limited faults, as they assume that producers and consumers are constantly online. If a consumer is offline, it may miss messages, and some protocols allow producers to retry failed deliveries, but this can break down if the producer crashes and loses messages.

An alternative to direct communication between producers and consumers is to use a message broker, also known as a message queue, which is a specialized database optimized for handling message streams. The broker operates as a server, with producers and consumers connecting to it as clients. Producers write messages to the broker, and consumers receive them by reading from the broker. Centralizing the data in this way allows the system to easily tolerate clients coming and going, and the question of durability is handled by the broker itself. Some brokers keep messages in memory, while others write them to disk to prevent data loss in the event of a broker crash. As a result of using a queue, consumers are generally asynchronous, with the producer only waiting for the broker to confirm that the message has been buffered and not for the message to be processed by consumers. Some brokers can also participate in two-phase commit protocols, making them similar to databases with some practical differences, such as a focus on short-term storage and limited support for arbitrary queries. Message brokers often support the ability to subscribe to a subset of topics matching a pattern and can notify clients when data changes.

There are two main patterns for handling multiple consumers reading from the same topic:

- Load balancing, where each message is delivered to one of the consumers

- Fan-out, where each message is delivered to all of the consumers.

To ensure that messages are not lost, message brokers use acknowledgments, requiring clients to explicitly tell the broker when they have finished processing a message so it can be removed from the queue. Using load balancing with redelivery can result in message reordering, which can be avoided by using a separate queue for each consumer.

Partitioned Logs

Log-based message brokers combine the durable storage approach of databases with the low-latency notification capabilities of messaging. In this system, a producer sends a message by appending it to an append-only sequence of records, or log, on disk, and consumers receive messages by reading the log sequentially. If a consumer reaches the end of the log, it waits for a notification that a new message has been added. The log can be partitioned to scale to higher throughput and different partitions can be hosted on different machines, with a topic defined as a group of partitions carrying messages of the same type. Within each partition, the broker assigns a monotonically increasing sequence number, or offset, to each message. Examples of log-based message brokers include Apache Kafka, Amazon Kinesis Streams, and Twitter's DistributedLog.

This approach supports fan-out messaging and allows multiple consumers to independently read the log without affecting each other. It also allows for load balancing by assigning entire partitions to nodes in the consumer group, with each client consuming all the messages in the partition it has been assigned. However, this approach has some downsides, including a limited number of nodes that can share the work of consuming a topic and the potential for a single slow message to hold up the processing of subsequent messages in the same partition. In situations with high message throughput, fast processing times, and the need for message ordering, the log-based approach is effective. The offset in the log, similar to a log sequence number in database replication, allows for monitoring of a consumer's progress and the raising of alerts if it falls significantly behind the head of the log. If a consumer falls too far behind, it can be reset to the head of the log to avoid missing messages, but this can result in the processing of some messages multiple times. To prevent the log from using all available disk space, old segments are periodically deleted or moved to an archive, which can lead to the loss of messages if a consumer falls too far behind. The throughput of a log remains constant, unlike messaging systems that keep messages in memory and only write to disk when the queue grows too large, with throughput dependent on the amount of history retained. If a consumer falls behind the producers, it can drop messages, buffer them, or apply backpressure to slow the producers down.

Databases and Streams

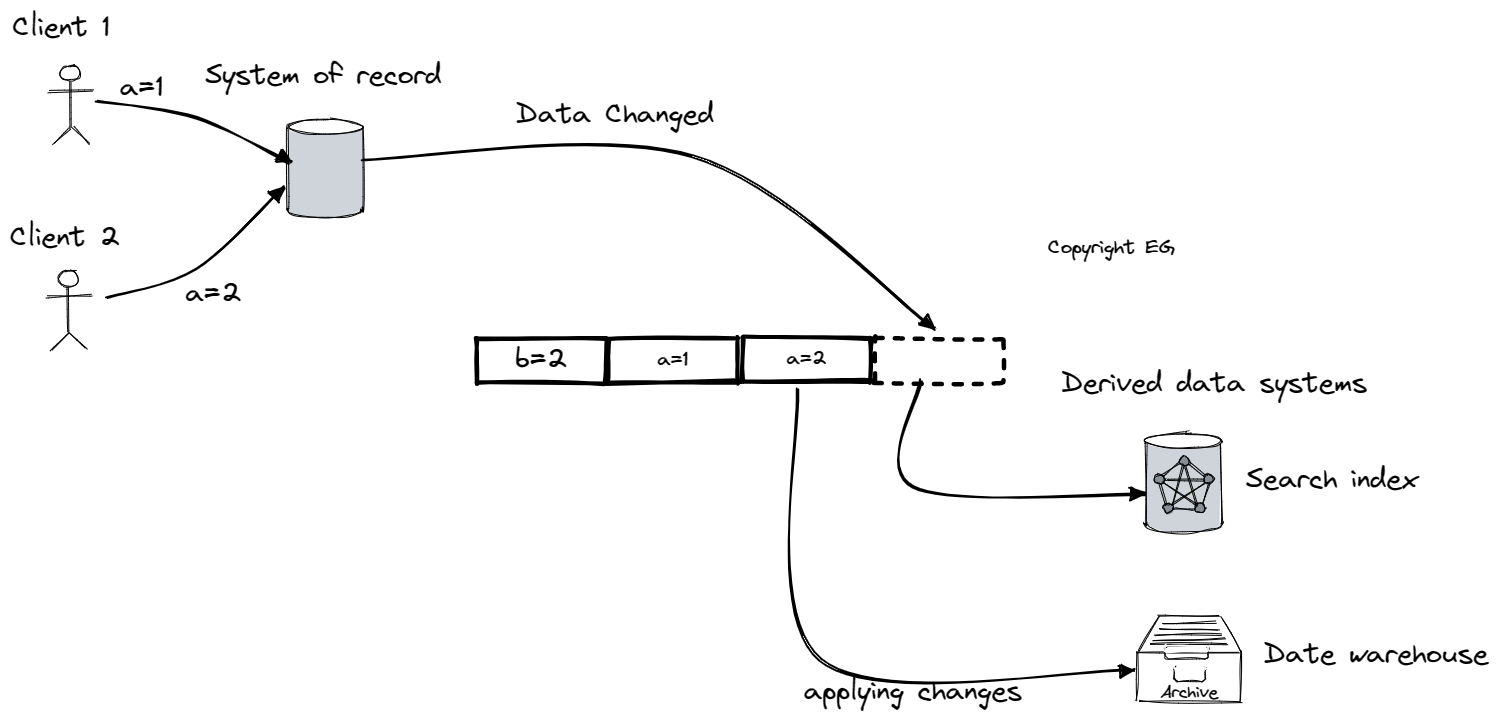

Change data capture (CDC) is a technique used to replicate data changes made to a database to other systems in real-time. It works by observing all data changes made to the database and extracting them in a form that can be replicated to other systems, such as search indexes, data warehouses, and message brokers. CDC ensures that changes made to the system of record are reflected in all derived data systems, providing a consistent view of the data across the organization.

There are several ways to implement CDC, including the use of triggers and the parsing of the database's replication log. Triggers are database-specific and can be fragile, with significant performance overheads. Parsing the replication log, on the other hand, can be a more robust approach, as it does not depend on the specific database being used. Tools such as LinkedIn's Databus, Facebook's Wormhole, Yahoo!'s Sherpa, Bottled Water, Maxwell, Debezium, Mongoriver, and GoldenGate all use CDC to replicate data changes between different systems.

In order to prevent the change log from using too much disk space or taking too long to replay, it is necessary to truncate the log. This can be done by starting with a consistent snapshot of the database that corresponds to a known position or offset in the change log. The storage engine can then periodically look for log records with the same key, discarding any duplicates and keeping only the most recent update for each key. An update with a special null value, known as a tombstone, indicates that a key was deleted.

The same idea of change data capture can also be applied to log-based message brokers, with tools such as RethinkDB, Firebase, CouchDB, and Kafka Connect all providing data synchronization based on change feeds. These tools allow users to subscribe to notifications and receive real-time updates whenever data changes occur in the database.

Overall, CDC is a powerful tool for ensuring that data changes are consistently replicated across multiple systems, providing a consistent view of the data and enabling real-time data processing and analysis.

Event Sourcing

Event sourcing is a technique that involves storing all changes to the application state as a log of change events. This approach can be useful for a number of reasons. First, it can make it easier to evolve applications over time. By storing a complete log of all changes, it becomes possible to understand how the application state has changed and to make changes to the application accordingly. Second, event sourcing can be helpful for debugging by making it easier to understand after the fact why something happened. By having a complete record of all changes, it is easier to trace back the steps that led to a particular state or issue. Finally, event sourcing can guard against application bugs by providing a complete record of changes that can be used to identify and fix problems.

To support event sourcing, specialized databases such as Event Store have been developed. These databases are designed to store and manage the log of events in an efficient and reliable way.

In event sourcing, the log of events is transformed into the application state that is displayed to the user. This process involves taking the events in the log and using them to recreate the current state of the application. The event log can also be used to reconstruct the current state of the system at any point in time by replaying the events in the log in the order in which they occurred.

Applications that use event sourcing often include mechanisms for storing snapshots of the application state at specific points in time. These snapshots can be used to more quickly reconstruct the current state of the system, rather than having to replay the entire log of events.

Event sourcing philosophy distinguishes between events and commands. A command is a request from a user that may still fail validation before becoming an event. For example, a request to reserve a seat in a theater may be initially treated as a command. If the request is successful and the seat is actually reserved, it becomes an event that is stored in the log. If the request fails validation (e.g., because the seat is already reserved), it does not become an event.

Consumers of the event log in event sourcing systems are usually asynchronous, which means that they may not see updates immediately after they are made. For example, a user may make a write to the log, then read from a log-derived view and find that their write has not yet been reflected. This can be a limitation of event sourcing and change data capture in some cases.

Immutable event history can also be a limitation in certain situations. Some workloads, such as those that mostly add data and rarely update or delete it, are easy to make immutable. However, workloads with a high rate of updates and deletes on a relatively small dataset can be more challenging to make immutable due to fragmentation, performance, compaction, and garbage collection.

There may also be circumstances in which data needs to be deleted for administrative reasons. In these cases, event folding, or rewriting history, can be useful. However, event folding can also introduce complexity and may not be appropriate in all situations.

Overall, event sourcing and change data capture can provide a number of benefits, including the ability to evolve applications over time, improved debugging, and protection against application bugs. However, they may also have limitations, such as the need for asynchronous consumers and the challenges of immutable event history in certain workloads. It is important to carefully consider the specific needs and requirements of an application before deciding whether event sourcing or change data capture is the right approach.

Processing Streams

There are various things that can be done with an event stream once it has been obtained. One option is to write the data in the events to a database, cache, search index, or similar storage system, from where it can be queried by other clients. Another possibility is to push the events to users in some way, such as by sending email alerts or push notifications, or to a real-time dashboard. Another option is to process one or more input streams to produce one or more output streams. This is typically what an operator job does, with the crucial difference being that a stream never ends.

Complex event processing (CEP) is a technique for analyzing event streams in which rules are specified to search for certain patterns of events. When a match is found, the CEP engine emits a complex event. Queries are stored long-term and events from the input streams are continuously processed in search of a query that matches an event pattern. There are various implementations of CEP, including Esper, IBM InfoSphere Streams, Apama, TIBCO StreamBase, and SQLstream. The boundary between CEP and stream analytics is sometimes blurry, with stream analytics tending to focus more on aggregations and statistical metrics. Examples of frameworks with a focus on analytics include Apache Storm, Spark Streaming, Flink, Concord, Samza, and Kafka Streams. Hosted services such as Google Cloud Dataflow and Azure Stream Analytics are also available.

Sometimes there is a need to search for individual events continually, such as when performing full-text search queries over streams. Message-passing systems are also based on messages and events, although they are not typically thought of as stream processors. There is some overlap between RPC-like systems and stream processing, with Apache Storm featuring a distributed RPC feature.

In a batch process, the time at which the process is run is unrelated to the time at which the events actually occurred. Many stream processing frameworks use the local system clock on the processing machine (processing time) to determine windowing. This can be a simple approach, but it can break down if there is any significant processing lag. It is important to carefully consider the distinction between event time and processing time, as confusing these can lead to inaccurate data. Processing time may be unreliable due to factors such as event queuing or system restarts, so it is often better to take into account the original event time when calculating rates. It is also important to keep in mind that you can never be certain when all of the events have been received.

In stream processing, it is possible for events to be delayed due to network interruptions or other issues. These events, known as "straggler events" can arrive after a window has been declared complete. There are several options for handling straggler events, including ignoring them and tracking the number of dropped events as a metric, publishing a correction that includes the straggler events and possibly retracting previous output, or adjusting for incorrect device clocks. To adjust for incorrect device clocks, one approach is to log three timestamps: the time at which the event occurred according to the device clock, the time at which the event was sent to the server according to the device clock, and the time at which the event was received by the server according to the server clock. By estimating the offset between the device clock and the server clock, it is possible to apply that offset to the event timestamp and estimate the true time at which the event actually occurred.

There are several types of windows that are commonly used in stream processing:

- Tumbling windows, which are fixed in length

- Hopping windows, which are fixed in length but allow for overlapping windows to provide some smoothing

- Sliding windows, which cover events that occur within a certain interval of each other

- Session windows, which are not fixed in duration and include all events for the same user until the user has been inactive for a specified period of time.

Joining streams can be challenging due to the fact that new events can appear at any time on a stream. This can make it difficult to ensure that the correct events are being matched and joined.

Stream-stream Joins (window join)

Let's say you want to detect recent trends in searched-for URLs and need to bring together events for search actions and click actions. To do this, a stream processor needs to maintain state by storing all events that occurred in the last hour, indexed by session ID. Whenever a search event or click event occurs, it is added to the appropriate index and the stream processor also checks the other index to see if there is a matching event for the same session ID. If a matching event is found, the stream processor emits an event indicating that the search result was clicked. This process allows the stream processor to identify and track trends in searched-for URLs by matching search actions with corresponding click actions.

Stream-table Joins (stream enrichment)

This process, sometimes known as enriching activity events with information from a database, involves combining two datasets: a set of user activity events and a database of user profiles. The activity events include the user ID, and the resulting stream should include augmented profile information based on the user ID. To achieve this, the stream processor needs to look at each activity event individually, look up the event's user ID in the database, and add the profile information to the activity event. One approach to performing the database lookup is to query a remote database, but this can be slow and potentially overwhelm the database. An alternative approach is to load a copy of the database into the stream processor so that it can be queried locally without a network round-trip. In this case, it is important to ensure that the stream processor's local copy of the database is kept up to date, which can be accomplished using change data capture.

Table-table join (materialized view maintenance)

Let's use Twitter timeline as an example. It is too expensive to retrieve a user's home timeline by iterating over all the people the user is following, finding their recent tweets, and merging them. Instead, a timeline cache is used as a kind of per-user "inbox" to which tweets are written as they are sent, allowing the timeline to be retrieved with a single lookup. To maintain this cache, the following event processing is required: when a user sends a new tweet, it is added to the timeline of every user who is following them; when a user deletes a tweet, it is removed from all users' timelines; when a user starts following another user, recent tweets by the latter are added to the former's timeline; and when a user unfollows another user, tweets by the latter are removed from the former's timeline.

To implement this cache maintenance in a stream processor, streams of events for tweets (sending and deleting) and follow relationships (following and unfollowing) are needed. The stream processor also needs to maintain a database containing the set of followers for each user so that it knows which timelines need to be updated when a new tweet arrives. The join of these streams corresponds directly to the join of the tables in the query used to retrieve a user's home timeline, with the timelines serving as a cache of the result of this query, updated whenever the underlying tables change.

Time-dependence of Joins

The previous three types of join require the stream processor to maintain some state, which can lead to issues when state changes over time and the point in time used for the join is unclear. If the ordering of events across streams is undetermined, the join becomes nondeterministic. This issue, known as slowly changing dimension (SCD), is often addressed by using a unique identifier for a particular version of the joined record. For example, using a unique identifier for the tax rate at the time of sale can make the system deterministic, but it can also make log compaction impossible.

Fault Tolerance

In batch processing, tasks can be restarted if they fail, input files are immutable, and output is written to a separate file. This allows for exactly-once semantics, or the appearance that records are only processed once, even if they are processed multiple times due to a restart. Stream processing, on the other hand, cannot wait for tasks to be completed before making their output visible because streams are infinite. One solution is to use microbatching, which involves breaking the stream into small blocks and treating each block like a mini batch process. This is used in frameworks such as Spark Streaming, where the batch size is typically around one second. Another approach is to periodically generate rolling checkpoints of state and write them to durable storage, allowing a stream operator to restart from its most recent checkpoint if it crashes. This is used in frameworks like Flink, where snapshots are written to storage like HDFS. In order to provide exactly-once semantics, both of these techniques rely on distributed transactions or idempotent operations to ensure that partial output from failed tasks is discarded and does not take effect twice. In order to recover state after a failure, stream processors can either keep state in a remote datastore and replicate it, or keep state local to the processor and replicate it periodically through techniques like snapshotting or state replication. For example, Samza and Kafka Streams replicate state changes by sending them to a dedicated Kafka topic with log compaction, while VoltDB replicates state by redundantly processing each input message on several nodes.

Summary

We have discussed event streams and how they are used for stream processing. Stream processing is similar to batch processing, but it is performed continuously on unbounded streams rather than on a fixed size input. We compared two types of message brokers: AMQP/JMS-style brokers, which assign individual messages to consumers and require acknowledgement for successful processing, and log-based brokers, which assign all messages in a partition to the same consumer node and retain messages on disk for possible rereading. Streams can come from various sources such as user activity events, sensor readings, and data feeds, and can also be created by capturing the changelog (history of changes) in a database through change data capture or event sourcing. Stream processing can be used for tasks such as complex event processing, stream analytics, and maintaining derived data systems. We also discussed the challenges of dealing with time in a stream processor, including distinguishing between processing time and event timestamps and handling straggler events that arrive after a window has been declared complete. Finally, we described three types of joins that may be used in stream processing: stream-stream joins, stream-table joins, and stream-batch joins.