Transactions

Implementing fault-tolerant mechanisms can be a significant undertaking for a developer. One way to achieve this is through the use of transactions, which allow multiple operations on multiple objects to be executed as a single unit.

Conceptually, a transaction is either committed (succeeds) or aborted (fails). This allows the application to ignore certain error scenarios and concurrency issues, as the transaction will either complete successfully or be rolled back, ensuring that the system maintains a consistent state. To further ensure the integrity of transactions, the ACID properties (atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability) are often used. Atomicity helps prevent partial completion of transactions in the event of a fault, while consistency ensures that the data maintains certain invariants. Isolation ensures that concurrent transactions do not interfere with each other, and durability ensures that committed transactions are not lost, even in the event of a hardware failure or database crash.

In systems with leaderless replication, it is the responsibility of the application to handle errors and recover from them. One way to do this is through the use of transaction aborts, which allow for the safe retry of transactions in the event of an error. Overall, transactions are a powerful mechanism for ensuring the reliability and integrity of a system, and their use can greatly simplify the implementation of fault-tolerant mechanisms.

Weak Isolation Levels

Transaction isolation is a feature of databases that aims to hide concurrency issues such as race conditions, which occur when one transaction reads data that is concurrently modified by another transaction, or when two transactions try to simultaneously modify the same data. While serializable isolation provides the highest level of protection against these issues, it comes with a performance cost. As a result, many systems opt for weaker levels of isolation that protect against some concurrency issues, but not all. Let's break down common weak isolation levels.

Read Committed

Read committed is a type of weak isolation level that provides two guarantees:

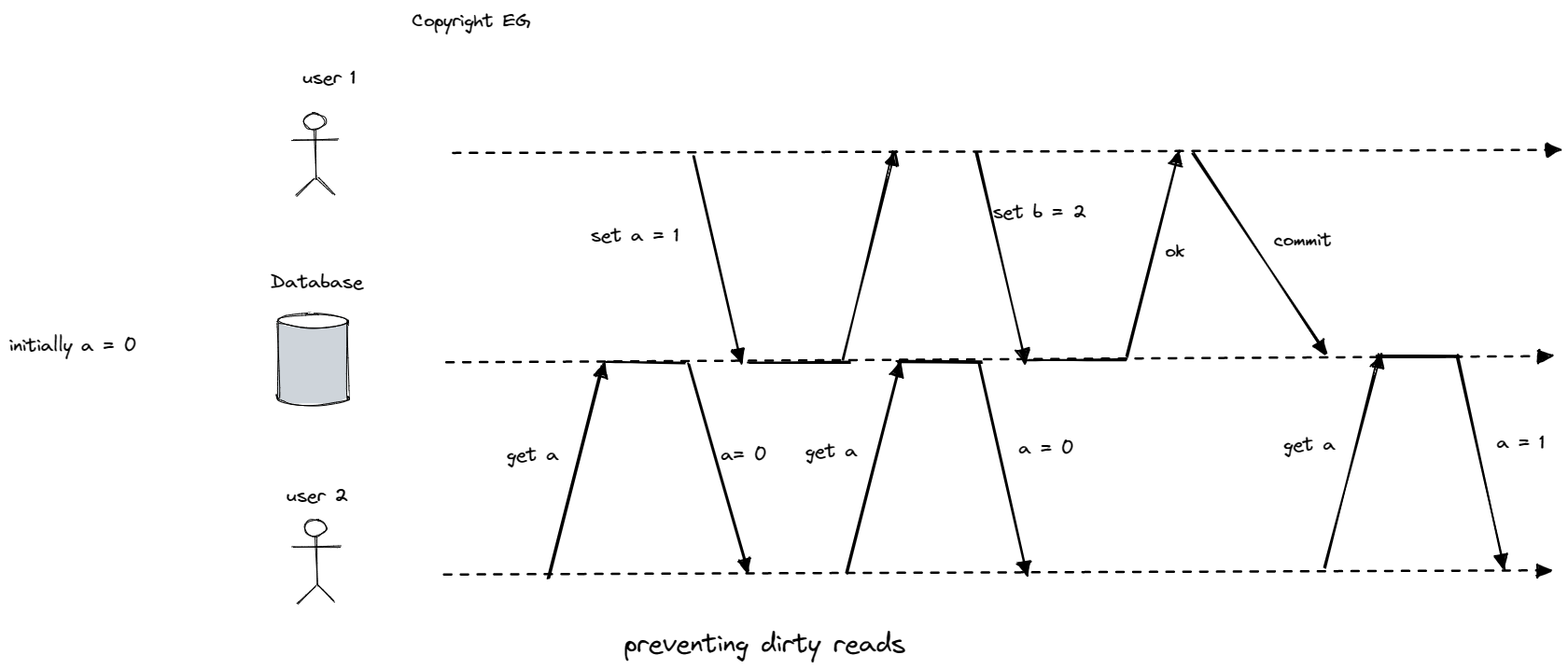

- When reading from the database, you will only see data that has been committed (no dirty reads). This means that you will not see data that is in the process of being modified by another transaction.

- When writing to the database, you will only overwrite data that has been committed (no dirty writes). This means that you will not overwrite data that is in the process of being modified by another transaction. To prevent dirty writes, most databases use row-level locks that hold the lock until the transaction is committed or aborted. Only one transaction can hold the lock for any given object at a time.

One potential issue with read committed is that requiring read locks does not work well in practice, as a long-running write transaction can force many read-only transactions to wait. To address this issue, many databases remember both the old committed value and the new value set by the transaction that currently holds the write lock. While the transaction is ongoing, any other transactions that read the object are simply given the old value. This allows read-only transactions to proceed without being blocked by write transactions.

Snapshot Isolation and Repeatable Read

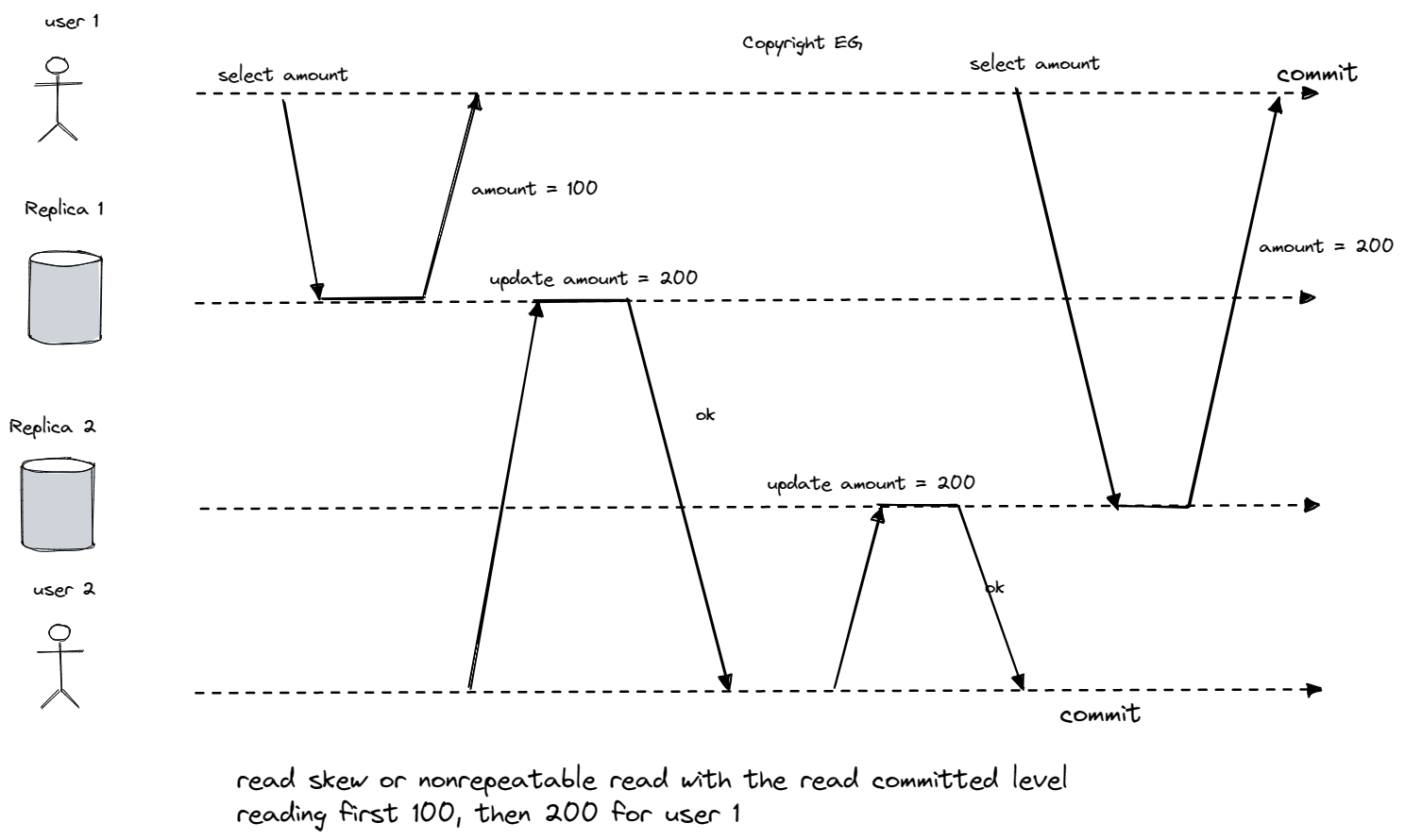

Even when using the read committed isolation level, there are still ways in which concurrency bugs can occur. One such issue is nonrepeatable read or read skew, where temporal and inconsistent results may be seen when reading data at the same time as a change is committed. This can be a problem in situations where temporal inconsistencies cannot be tolerated, such as when taking backups or running analytic queries or integrity checks.

To address these issues, snapshot isolation is often used, which allows each transaction to read from a consistent snapshot of the database. The implementation of snapshots typically involves the use of write locks to prevent dirty writes. In a multi-version database, the database may need to keep several different committed versions of an object (using a technique called multi-version concurrency control or MVCC). Read committed uses a separate snapshot for each query, while snapshot isolation uses the same snapshot for an entire transaction.

Indexes in a multi-version database typically point to all versions of an object and require an index query to filter out any object versions that are not visible to the current transaction. Snapshot isolation is known as serializable in Oracle, and repeatable read in PostgreSQL and MySQL.

Preventing Lost Updates

There is a potential issue that can occur when two transactions concurrently perform a read-modify-write cycle on the same data, where one of the modifications is lost (the later write overwrites the earlier write). One solution to this problem is to use atomic write operations, which allow updates to be made in a single, indivisible step. For example, the following UPDATE statement in SQL is atomic:

UPDATE sum SET value = value + 1 WHERE id = 1;

Database MongoDB and Redis, provide atomic operations for making local modifications or modifying data structures.

Another approach to addressing the issue of lost updates is to use explicit locking, where the application explicitly locks objects that are going to be updated. Some transaction managers also provide the ability to automatically detect lost updates and allow them to execute in parallel. If a lost update is detected, the transaction is aborted and forced to retry its read-modify-write cycle. However, it is important to note that MySQL/InnoDB's repeatable read isolation level does not detect lost updates.

Another solution is to use a compare-and-set operation, where the update is only applied if the current value matches the value that was previously read. For example:

UPDATE a SET value = 'new value' WHERE id = 1 AND value = 'old value';

In a replicated database with multi-leader or leaderless replication, compare-and-set operations may not be applicable. In these cases, it is common to allow concurrent writes to create several conflicting versions of a value (also known as siblings), and to use application code or special data structures to resolve and merge these versions after the fact.

Write Skew and Phantoms

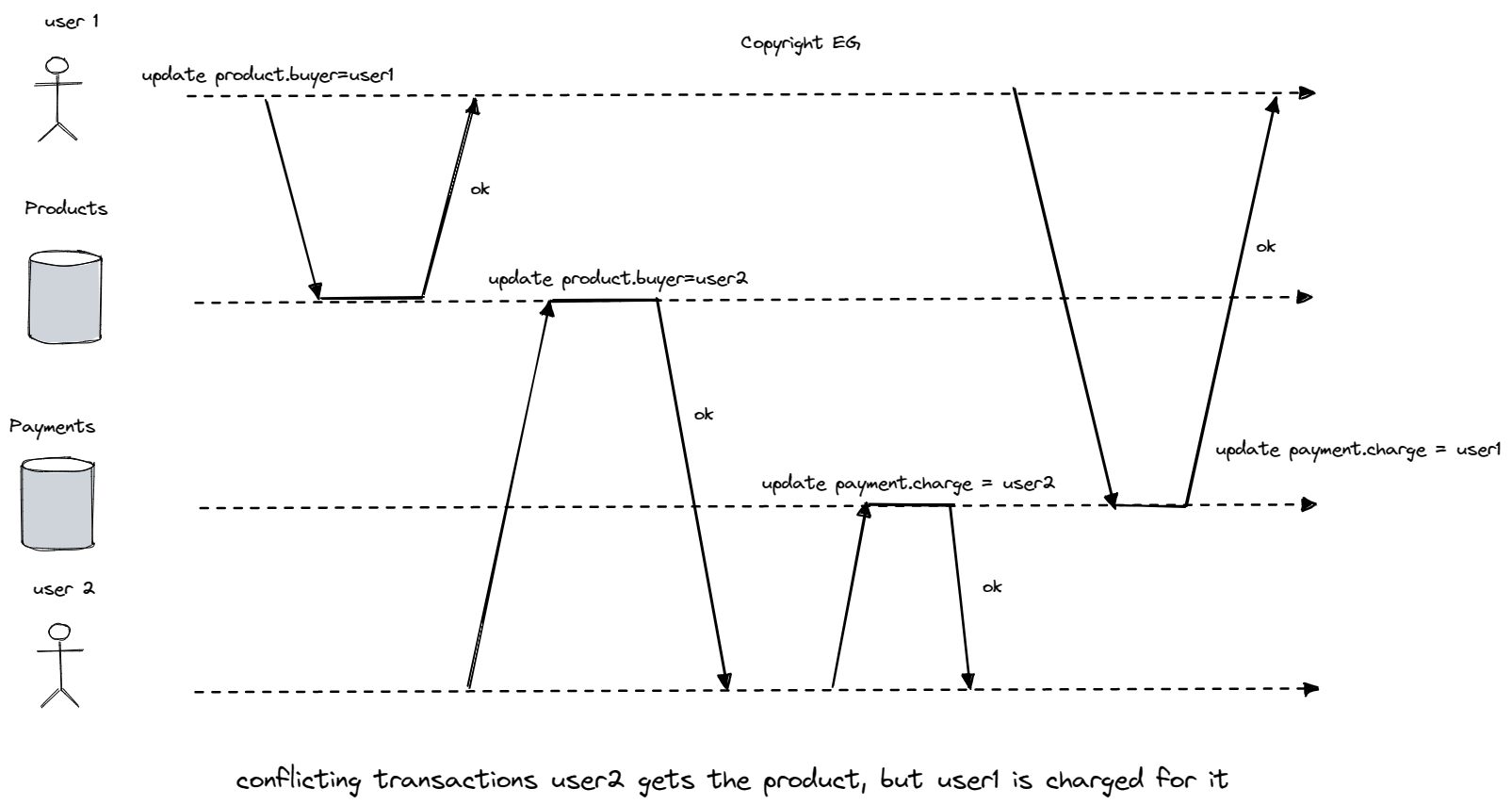

Write skew is a type of concurrency issue that can occur when two transactions read the same objects and then update some of those objects, resulting in a dirty write or lost update anomaly. This can be problematic if the updates are intended to maintain certain invariants in the data.

For example, consider the case of two on-call doctors, Alice and Bob, who are both feeling unwell and try to go off call at the same time. If the database is using snapshot isolation, both transactions may read the current number of on-call doctors as 2, and then both transactions may commit, resulting in no doctors being on call, which violates the requirement of having at least one doctor on call.

There are a few ways to prevent write skew:

- Use atomic operations: While atomic operations can be useful in preventing some concurrency issues, they are not always sufficient when multiple objects are involved.

- Use true serializable isolation: This is the most effective way to prevent write skew, as it ensures that transactions are executed serially in a way that maintains the integrity of the data.

- Explicitly lock rows: If true serializable isolation is not available, it may be possible to prevent write skew by explicitly locking the rows that the transaction depends on. This can ensure that concurrent transactions do not interfere with each other.

Serializability

Serializable isolation is the strongest isolation level available, as it guarantees that even though transactions may execute in parallel, the end result is the same as if they had executed one at a time, serially, without concurrency. In other words, the database prevents all possible race conditions. There are three techniques that can be used to achieve serializable isolation:

- Executing transactions in serial order: This involves executing transactions one at a time, in the order in which they were submitted. This ensures that there are no race conditions, as each transaction is completed before the next one begins.

- Two-phase locking: This involves acquiring locks on all objects that a transaction intends to modify before any changes are made. This prevents other transactions from modifying the same objects concurrently, ensuring that the transactions are executed serially.

- Serializable snapshot isolation: This involves using a snapshot of the data that is consistent across the entire transaction, rather than using a separate snapshot for each query. This ensures that all queries within a transaction see the same data, preventing race conditions.

Actual Serial Execution

One way to remove concurrency problems is to execute transactions in serial order on a single thread, which is implemented by systems such as VoltDB/H-Store, Redis, and Datomic. This approach is simple, but it limits the transaction throughput to the speed of a single CPU.

To improve performance, some systems use stored procedures to encapsulate transactions. With this approach, the application submits the entire transaction code to the database ahead of time as a stored procedure, which allows the procedure to execute very quickly because all the required data is in memory. However, stored procedures have a number of drawbacks, such as being tied to a specific database vendor, being difficult to debug and deploy, and being hard to integrate with monitoring. Some modern implementations of stored procedures, such as VoltDB, Datomic, and Redis, use general-purpose programming languages instead of proprietary languages.

Another way to scale transaction processing to multiple CPU cores is to partition the data and assign each partition to its own transaction processing thread. For transactions that need to access multiple partitions, the database must coordinate the transaction across all the partitions, which can be slower than single-partition transactions.

In summary, serial execution of transactions can be a viable way to achieve serializable isolation, but it comes with certain constraints:

- Every transaction must be small and fast, as a single slow transaction can stall all transaction processing.

- The active dataset must be able to fit in memory, or else the system may become slow if data that is rarely accessed needs to be accessed in a single-threaded transaction.

- Write throughput must be low enough to be handled on a single CPU core, or else transactions may need to be partitioned without requiring cross-partition coordination.

- Cross-partition transactions are possible, but there are limits to the extent to which they can be used.

Two-Phase Locking (2PL)

Two-phase locking (2PL) (different than two-phase commit (2PC)) is a technique used to achieve serializable isolation in a database. It allows multiple transactions to concurrently read the same object as long as nobody is writing to it, but when a transaction wants to write to (modify or delete) an object, it must acquire exclusive access by acquiring a lock in exclusive mode. This prevents race conditions by blocking both readers and writers from accessing the object simultaneously.

In 2PL, a lock is placed on each object in the database and transactions must acquire the lock before reading or writing to the object. The lock must be held until the transaction is committed or aborted, and transactions may need to upgrade their shared lock to an exclusive lock if they want to write to an object after reading it. However, 2PL can lead to deadlocks if two transactions are waiting for each other to release their locks.

The performance of 2PL is generally worse than weak isolation levels in terms of transaction throughput and query response time. It can also lead to unstable latencies and slow performance at high percentiles, as a single slow transaction or a transaction that acquires many locks can cause the rest of the system to halt.

To prevent phantoms (changes to the results of a search query made by another transaction), some databases use predicate locks, which apply to all objects that match a certain search condition, even if they do not yet exist in the database. However, predicate locks can be inefficient, so many databases use index-range locks instead, which are less precise but have lower overhead. Index-range locks simplify the predicate by matching a larger set of objects, and while they're not that precised as predicate locks, they come with lower overhead making it a good compromise.

Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI)

Serializable snapshot isolation (SSI) is a technique for achieving full serializability in a database, with only a small performance penalty compared to snapshot isolation. It is an optimistic concurrency control method, meaning that transactions continue to execute in the hope that everything will turn out all right, rather than blocking if there is a potential issue. If something goes wrong, the database is responsible for detecting the problem and aborting the transaction, which must then be retried.

SSI is based on snapshot isolation, where reads within a transaction are made from a consistent snapshot of the database. In addition, SSI includes an algorithm for detecting serialization conflicts among writes and determining which transactions to abort. This involves tracking when a transaction ignores another transaction's writes due to MVCC visibility rules, and checking whether any of these ignored writes have now been committed. It also involves using index-range locks to detect writes that affect prior reads and notify other transactions that the data they read may no longer be up-to-date.

The main advantage of SSI over two-phase locking is that one transaction does not need to block waiting for locks held by another transaction. It is also not limited to the throughput of a single CPU core like serial execution, as transactions can read and write data in multiple partitions while ensuring serializability. However, the rate of aborts can significantly affect the overall performance of SSI, and it is important for read-write transactions to be relatively short in duration.

Summary

In summary, transactions are a way for an application to ensure that data in a database remains consistent and correct, even in the face of various errors and concurrency issues. Isolation levels are a way to manage concurrency issues in a database by specifying how transactions interact with each other. They provide different guarantees about the effects of concurrent transactions on the data being accessed.

The most basic isolation level is "read uncommitted," which allows transactions to read data that has not yet been committed by other transactions. This can lead to dirty reads, where a transaction reads data that is later rolled back or changed by another transaction.

The read committed isolation level ensures that transactions can only read data that has been committed by other transactions. This prevents dirty reads, but does not protect against other concurrency issues such as lost updates (where one transaction overwrites data written by another transaction).

Snapshot isolation ensures that each transaction sees a consistent snapshot of the data at a specific point in time, and allows transactions to be executed concurrently without interference from each other. This prevents dirty reads and lost updates, but does not protect against read skew (where a transaction reads different parts of the database at different points in time) or phantom reads (where a transaction reads data that satisfies a certain condition, and another transaction writes data that would also satisfy that condition).

The serializable isolation level provides the strongest guarantees, ensuring that transactions are executed in a way that is equivalent to them being executed one at a time, serially. This prevents all concurrency issues, but can come at a cost to performance. There are several ways to implement serializable transactions, including two-phase locking and serializable snapshot isolation.