Rate Limiter

A rate limiter in a network system controls the amount of traffic allowed to be sent by a client or service. In the context of HTTP, it limits the number of requests sent over a certain period. If the number of requests exceeds the set limit, any additional calls are blocked. The benefits of using a rate limiter include protection against Denial of Service (DoS) attacks, reduction of costs, and preventing server overload by filtering out excessive requests. Examples of rate limits include a maximum number of posts per second, accounts created per day from a single IP, or rewards claimed per week from a single device. Rate limiter also could be used to prevent Noisy neighbor situation where one client is using all the server resources by calling service operation multiple times preventing other clients to do other operations. The initial idea could be to just scale out our service so it can serve more demanding client base during burst of traffics, but it's important to keep in mind that scaling (even auto-scalling, scaling without manual intervention during peek hours) takes time and we have to deal with incoming requests during the transition phase which increases the need for service like rate limiter. Also you could point out that it's possible to utilize load balancer with specific configuration to deal with (as close to) uniform partition of load, but it's hard to make this work on more granular rule like per operation, per time/storage used and similar.

Functional and non-functional requirements:

The selection of a rate limiter algorithm depends on various factors and can be determined through a conversation between an interviewer and a candidate. For this scenario let's assume the focus is on a server-side rate limiter that can handle a high volume of requests, be adaptable to various throttling rules, work efficiently (scalability) in a distributed system, have minimal latency and memory usage. Furthermore, it should have the ability to notify users when their requests are being throttled. We should also make sure to not cause a cascading failure after fault happens in the rate limiter, one way to achieve that is to proceed as "business as usual" and not rate-limit the requests if the rate limiter middleware is down, the other way is to ensure fault tolerance and redirect the client request to another healthy rate limiter instance.

High Level Design

Implementing a rate limiter can be done on either the client or server side. A client-side implementation is not always reliable as malicious actors can easily forge requests, and there may not be control over the client implementation. A server-side implementation is more effective in enforcing rate limits. Another option is to use a rate limiter middleware to throttle requests to APIs. This allows for rate limiting to be implemented within an API gateway, a fully managed service that can handle rate limiting, SSL termination, , IP whitelisting. The decision on where to implement a rate limiter depends on factors such as the company's current technology stack, engineering resources, priorities, and goals. Considerations include the efficiency of the current programming language for implementing rate limiting on the server-side, the rate limiting algorithm that best fits the business needs, the presence of an API gateway in the microservice architecture, and the availability of engineering resources to build a rate limiter or the use of a commercial API gateway. Also it's important to mention an option of having a rate limiter as deamon process running on the same server we're serving our API for example, this would allows us to have a rate limit client library integrated in our backend code which is calling the rate limit functionalities/checks to either reject or allow a request. This would allows us to have seperate memory space for our rate limiter and it's also could be coded with another programming language if for example we have a seperate group of developers only working on rate limiter system. Since we might want our rate limiter to be easily integrate with any existing system for this scenario we will be focusing on having at seperate component/middleware running on another host than our cient backend services.

The diagram below shows a simple high level design where we have a rate limiter middleware, which tracks the number of requests per users and if they exceeed the limit sends a HTTP code 429 too many requests code back.

Algorithms

- Fixed window counter

- Sliding window log

- Sliding window counter

- Token bucket

- Leaking bucket

Fixed window counter algorithm divides time into fixed-sized windows, and assigns a counter for each window. Each request increments the counter by one. Once the counter reaches a pre-defined threshold, new requests are dropped until the next time window starts. However, this algorithm has a major problem, which is that a burst of traffic at the edges of time windows could cause more requests than the allowed quota to go through. Let's say our app allows 100 login retries in one hour, if a users starts sending 100 requests at 12:30 and ends before 1pm then resumes to send 100 logins requests at 1-1:30 am the system would have allowed 200 request from the period 12:30-1:30 which is the double of login requests in one hour. Despite this limitation, the algorithm is memory efficient, easy to understand and resetting available quota at the end of a unit time window fits certain use cases.

Sliding window log algorithm addresses the problem of allowing more requests to go through at the edges of a window, which exists in fixed window counter algorithm. It works by keeping track of request timestamps in a cache. When a new request comes in, all timestamps older than the start of the current time window are removed, and the timestamp of the new request is added to the log. If the log size is equal to or lower than the allowed count, the request is accepted, otherwise it is rejected. The algorithm is accurate in ensuring that requests do not exceed the rate limit but it consumes a lot of memory because timestamps of rejected requests might still be stored in memory.

Sliding window counter algorithm is a combination of the fixed window counter and sliding window log algorithms. We're calculating the number of requests in the rolling window by taking into account the number of requests in the current window, the number of requests in the previous window, and the percentage of overlap between the two windows. This approach helps to even out traffic spikes as it bases the rate limit on the average rate of the previous window. It is also memory efficient. However, it is not precise one since it uses approximation of the actual rate as it assumes requests in the previous window are evenly distributed.

The token bucket algorithm is a method for rate limiting that is widely used by internet companies like Amazon. It involves a container, or "bucket" with a pre-determined capacity. Tokens are added to the bucket at set intervals and when the bucket is full, no more tokens can be added. Each request consumes one token, and if there are not enough tokens in the bucket, the request is rejected. The token bucket algorithm utilizes two parameters: the bucket size, which is the maximum number of tokens allowed in the bucket, and the refill rate, which is the number of tokens added to the bucket per second. The number of buckets needed depends on the rate-limiting rules and varies. For example, different buckets may be needed for different API endpoints or for throttling requests based on IP addresses. If we want to limit the total number of requests for example a global bucket could be used. The algorithm is easy to implement and memory efficient, and allows for traffic burst as long as we have enough tokens. However, it may be difficult to properly adjust the bucket size and refill rate to match the desired traffic rate.

Leaking bucket algorithm is similar to the token bucket algorithm in that it regulates the rate at which requests are processed. However, unlike the token bucket algorithm, requests in the leaking bucket algorithm are processed at a fixed rate. This is typically implemented using a first-in-first-out (FIFO) queue. When a request arrives, if the queue is not full, it is added to the queue. If the queue is full, the request is dropped. Requests are then pulled from the queue and processed at regular intervals. The algorithm takes two parameters: the bucket size, which is the size of the queue, and the outflow rate, which defines how many requests can be processed per second. The algorithm is memory efficient due to the limited queue size. However, it may struggle with a burst of traffic and it may be challenging to properly adjust the bucket size and (determine stable) outflow rate.

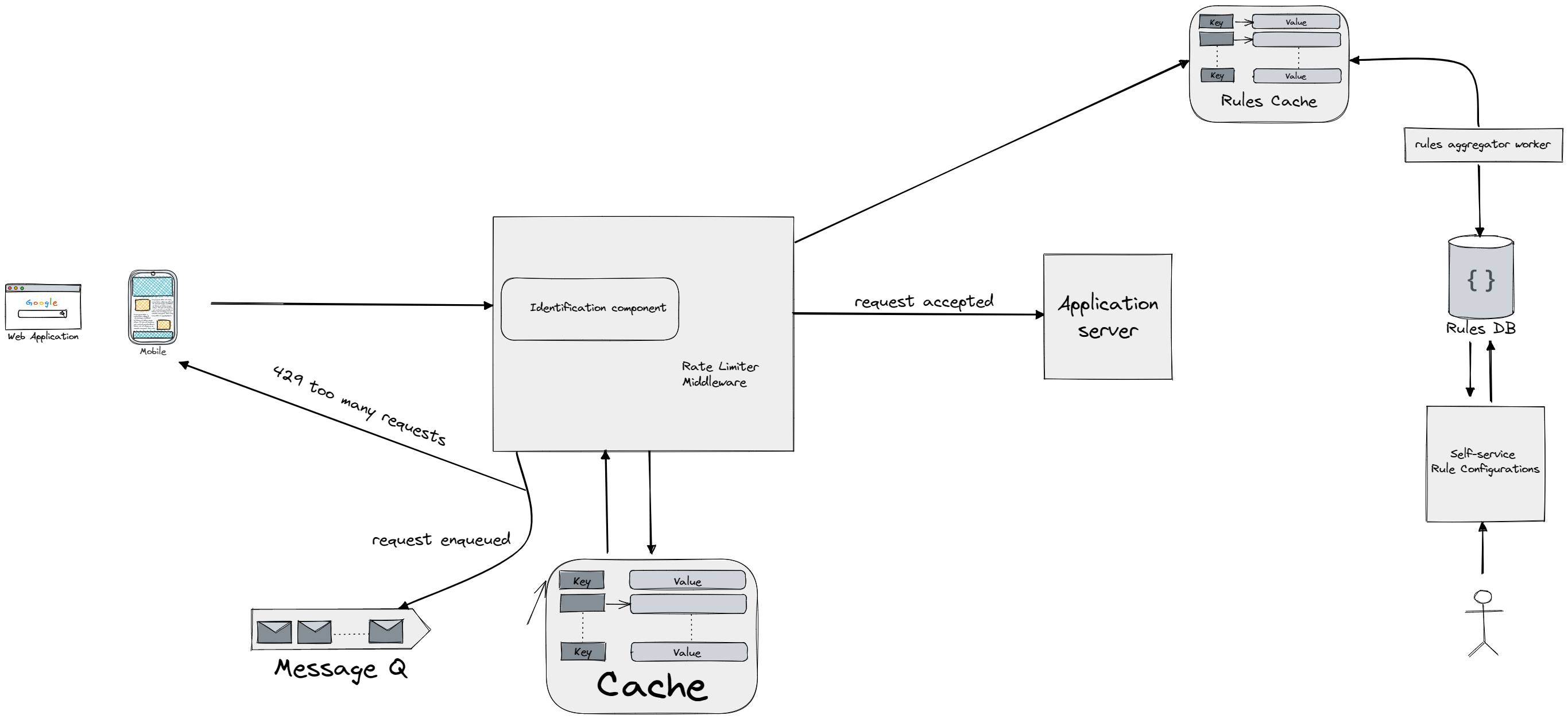

Rate limiting algorithms work by keeping track of the number of requests sent from a specific user, IP address, etc. using a counter. If this counter exceeds a set limit, the request is denied. Instead of using a database, an in-memory cache is used for storage as the operation required are actually just getting the counter and increasing and saving it back, so since cache is faster than database the natural choice is to go with it. The overall architecture for rate limiting involves the client sending a request to the rate limiting middleware, which then retrieves the counter from the corresponding bucket in cache and checks if the limit has been reached. If the limit is exceeded, the request is rejected, otherwise, it is sent to the API servers and the counter is incremented and saved back to cache.

When a request is rate limited, APIs return a HTTP response code 429 (too many requests) to the client. Depending on the use case, rate-limited requests can be enqueued to be processed later. For example, if orders are rate limited due to system overload, they can be kept to be processed later. The client can determine if it is being throttled by looking at the HTTP response headers. The rate limiter returns the following headers to the client: X-Ratelimit-Remaining which shows the remaining number of allowed requests within the window, X-Ratelimit-Limit which indicates how many calls the client can make per time window and X-Ratelimit-Retry-After which is the number of seconds to wait until the client can make a request again without being throttled. If a user has sent too many requests, a 429 too many requests error and X-Ratelimit-Retry-After header are returned to the client. Clients can determine if they are being rate limited by checking the HTTP headers in the response.

Rules for rate limiting are typically stored in configuration files on disk. These rules are periodically pulled by workers and stored in cache for quick access. When a client sends a request to the server, it first goes through the rate limiter middleware. The important part of this middleware will also be a client/operation identification which will give a unique ID to every operation/client that we can use to query the cache. The middleware loads the rules from cache, retrieves counters and the timestamp of the last request from the cache, and based on this information, it decides whether to forward the request to the API servers or if it should be rate limited. Configuration of rules could be a timeconsuming process so we could expose an API for rules creation for our users or even go step further and create a self-service portal with good UI/UX to guide the use through rules creation which will be later taken by rules aggregation (fetching and storing in cache) worker instance to fill out the cache of rules so it can it be retrieved fast by our middleware. A good question for the interviewer would be what if our service becomes super popular and we have to store millions of cache entries (token buckets for example)? Remember that we're using the cache to store the counter, and any respected (distributed) cache service has an eviction policy, so it goes hand in hand with our algorithms for rate limiting and cleans the cache of records which are not recently used (specifying time interval for example) If the request is rate limited, the rate limiter sends a HTTP response code 429 (Too Many Requests) to the client and the request can either be dropped or enqueued for processing later. Finally the client used to call our middleware could implement more sophisticated logic when the request gets rejected like exponential backoff, where we double the waiting time until we retry our request. To prevent from the requests made at same time to be retried at same time we could utilize jitter which adds randomness to the waiting time until the next retry.

Distributed Environment

Now if we lift up our rate limiter middleware to be used in distributed system we have solve the following problems: latency and consistency. To fix the latency we can use the users local proximity to our middleware resulting in replication of our middleware accross the globe. Now we have to enable communication between different instance of our middlware, since the load for example for one user requests could be spreaded accross multiple instances. We could do this by implementing gossip protocol (spreading from node to node like a gossip), but this would become rather costly if we had thousands of middleware instances that would have to talk with each other. Another option would be to pick a leader/coordinator that would broadcast the current state changes to all followers (more about it in the resource below), but problems like leader election arrise which could be solved with algorithms like Raft or Paxos. The other option is to have a leaderless or multileader topology. But as we know the replication is one of the main problems in distrubuted systems since we now have to synchronize different replicas in multileader/leaderless configuration and taking care of read-you-writes, monotonic reads, prefix reads issues arising in distributed systems. But note that we don't really need the middleware to hold this data, we could just centralize the communication in a distribute cache and handle all (in most cases) issues arrising in replicated storage systems. We have already covered Facebook Memcached and the problems in distributed cache which can be applied to this scenario too. To learn more about this issues and how to solve them check out (if you haven't already) following sections of the course:

- Google Spanner for serializability and atomic commits

- Facebook Memcached for implementing distributed cache and using locks for solving thundering herd and race problems

- Replication

Monitoring

Monitoring the performance of the rate limiter and collecting analytics is crucial to ensure that it is functioning properly. This includes evaluating the efficiency of the rate limiting algorithm and the rules set in place. If the rules are too restrictive, causing a high number of valid requests to be rejected, adjustments may need to be made to loosen them. Additionally, if the rate limiter struggles to handle unexpected increases in traffic, it may be necessary to consider alternative algorithms, such as the token bucket algorithm, that can better handle burst traffic.